The Envelope Corner: Polyurethane Spray Foam is Not a Panacea

By James D’Aloisio | June 2022

The use of closed-cell spray polyurethane foam has been expanding in recent years (pardon the pun!). It has excellent conductive thermal resistance and can be used, in some cases, as an effective air barrier. But there are limitations to its effectiveness in a building’s thermal envelope that not all practitioners realize.

- Cured SPF may develop cracks or bond failure over time, which can create air flow paths. This can occur when the substrate material to which the SPF is attached (usually steel or wood studs or joists) expands or shrinks due to temperature variations, and moisture variations in the case of wood members. And since SPF has very low thermal mass and does not absorb moisture, the air that exits through such fissures has the same temperature and humidity as it did when it entered, which can create high potential for condensation. Such an effect usually does not occur during construction, but over time, frequently exacerbating over several seasons.

What to do: Avoid the use of SPF on long framing elements, especially if they are subject to temperature variations.

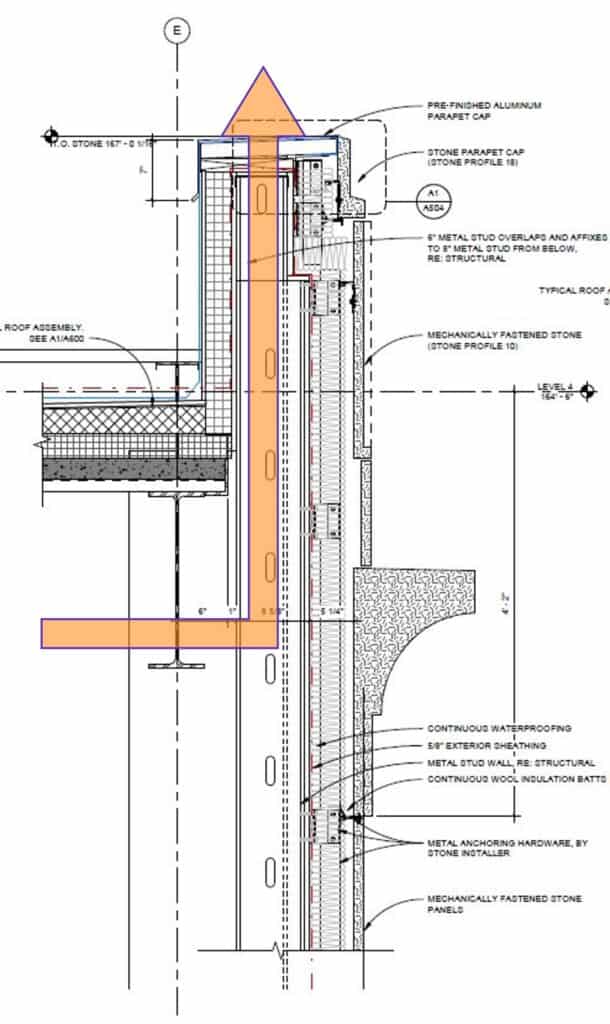

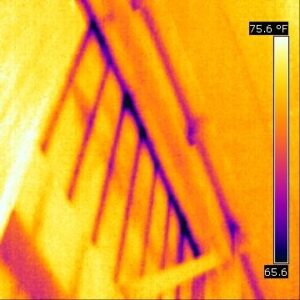

- Although SPF insulation has high R-values, when applied between studs, joists, or rafters the thermal conductivity of the framing members (called “field thermal bridging”) reduces the thermal resistance, in many cases by half or more. A variant of this is when cold-formed steel wall studs extend up past the roof spandrel beam to form a parapet – See Figures 1 and 2 below.

What to do: Calculate the increase in U-factor for the field. Usually, some amount of continuous insulation is needed to comply with the requirements of the Energy Code.

- Installation of SPF is very temperature sensitive. Not only does the ambient air temperature but the product and the surfaces to which it is applied need to be within the acceptable temperature range. Otherwise, the components may not react fully, and the SPF may not bond to the substrate. Also, improperly cured closed-cell material can release VOCs after the normal curing time.

What to do: Review installation by a third party, both during and after the application, to ensure that the material is properly installed and cured.

- The vapor impermeability of closed-cell SPF can trap undetected moisture. Conditions where SPF is applied directly to the underside of a roof deck are especially vulnerable to this, where the wood or steel roof deck and structural rafters or joists can experience significant rotting or rusting before any distress is noticed.

What to do: Only use closed-cell SPF in locations where vapor impermeability is acceptable. In other areas consider the use of alternatives such as open-cell SPF, mineral fiber, or cellulose.

- Most blowing agents for closed-cell SPF are hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) that have a very high global warming potential (GWP) – many are thousands of times more potent than CO2. The blowing agents dissipate into the atmosphere over time, and do not break down for thousands of years. This has led to the ironic condition that some well-insulated buildings are responsible for more GWP emissions than the reduction of operational emissions that the insulation was intended to effect!

What to do: Consider the use of open-cell, water-based SPF, although the thermal performance is somewhat less than closed-cell. If the properties of closed-cell SPF are needed, keep its use to a minimum and consider requiring the manufacturer to divulge the blowing agent and its GWP.

We have many material and system options that we can use to create high-performance thermal envelopes and produce buildings that perform well and have minimal problems for many years. Used correctly and judiciously, SPF can be a part of such a strategy. But in many cases, incorporating continuous rigid insulation plus a separate air barrier material will produce better results. Please contact KHH to help you meet the goals of your project.

Figure 1 – Thermal Loss Through Cold-formed Steel Stud-framed Parapet

Figure 2 – IR Image of Steel Studs Below Parapet Wall